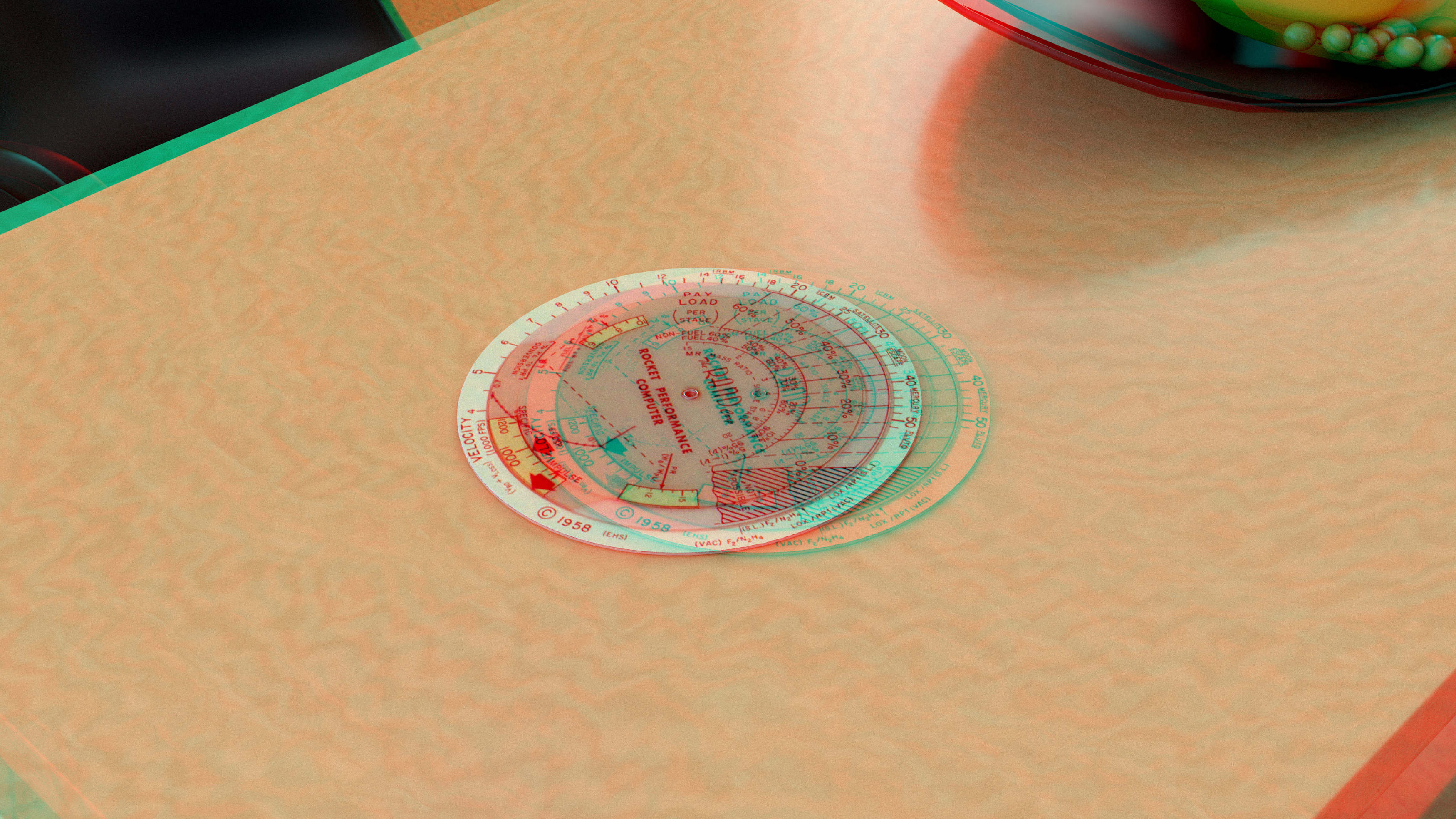

Multi-channel stereoscopic 4K projection (32:18 min), real-time computer simulation, mylar spheres

The House in the Sky is a video installation of anaglyph stereoscopic projections mapped onto Pioneer Works’ exhibition space. The projections re-create the mid-century modern Los Angeles home of RAND Corporation strategists Alfred and Roberta Wohlstetter, which was the site of one of the earliest think tanks. An “atomic Villa Diodati,” as Geoff Manaugh noted, the house was where possible futures were discussed along with the end of the world. Occurring in the 1950s during the Cold War, these conversations dwelled on a future that seemed especially precarious.

Modeled on photographs of the residence taken by Julius Shulman and Leonard Mccombe, the videos re-stage these interdisciplinary meetings. In the process, these videos become a virtual territory in which performances, readings, and a real-time simulation titled Leibniz Cocktail Conjecture aim to investigate relationships between architecture and critical inquiry, technological acceleration, and our place within history – both in regards to the past as well as our speculative future.

Modeled on photographs of the residence taken by Julius Shulman and Leonard Mccombe, the videos re-stage these interdisciplinary meetings. In the process, these videos become a virtual territory in which performances, readings, and a real-time simulation titled Leibniz Cocktail Conjecture aim to investigate relationships between architecture and critical inquiry, technological acceleration, and our place within history – both in regards to the past as well as our speculative future.

Conversation participants: Laura Ballantyne-Brodie (NYU), Lars Büsing (Google DeepMind), Claire Evans (YACHT), Jacob Gaboury (Stony Brook University/Max Planck Institute), Sam Hart (Avant.org/Sloan-Kettering), Janna Levin (Columbia University), Kate Marvel (NASA Goddard Institute), Nicola Masciandaro (Brooklyn College), Oliver Medvedik (Genspace), Gavin Schmidt (NASA Goddard Institute), Kevin Slavin (MIT Media Lab) and Roberta Wohlstetter read by Joan Wohlstetter-Hall as well as contributors Geoff Manaugh (BLDGBLOG) and Phillip Stearns.

Developed with the support from Pioneer Works, Eyebeam, Museum of Art and Design, Guesthouse Residency and the Headlands Center for the Arts.

We wish to thank Bitu Cao Minh (set assistance), CHiKA (projectors), Igor Donevski (3D modelling), Lindsay Eyink & Kevin Nelson, Gabriel Florenz, Wolfgang Gil (sound engineering), Lev Kalman (compositing support), Yael Krevsky, Marco Orozco, Lynn Russell, Roddy Schrock, Cliff Watts, Cate Wynn (set assistance), Jake Yuzna and everybody at Pioneer Works for their support in realizing this work.

Images: Exhibition view The House in the Sky at Pioneer Works, New York City

Developed with the support from Pioneer Works, Eyebeam, Museum of Art and Design, Guesthouse Residency and the Headlands Center for the Arts.

We wish to thank Bitu Cao Minh (set assistance), CHiKA (projectors), Igor Donevski (3D modelling), Lindsay Eyink & Kevin Nelson, Gabriel Florenz, Wolfgang Gil (sound engineering), Lev Kalman (compositing support), Yael Krevsky, Marco Orozco, Lynn Russell, Roddy Schrock, Cliff Watts, Cate Wynn (set assistance), Jake Yuzna and everybody at Pioneer Works for their support in realizing this work.

Nuclear Ghost Tales in the House in the Sky by Geoff Manaugh

In the summer of 1816, a group of young British writers rented a house on the shores of Lake Geneva, called the Villa Diodati. Their goal was to use it as a temporary home for several months of leisurely conversation and occasional writing, but also as base for short expeditions up into the nearby hills and mountains, where they hoped to experience the region’s glaciers and dramatic geological landscapes firsthand.

These writers were Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Polidori, and perhaps most consequently, the 18-year old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin—soon to become Mary Shelley, author of, among other books, Frankenstein.

The summer itself, in many ways, was a failure: due to the distant eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, which spread volcanic ash on winds across the entire northern hemisphere, their months in the Villa Diodati were marked not by sunshine and fresh mountain air but by near-continuous rain and violent thunderstorms. The skies were grey, the temperatures often frigid.

These meteorological events had a profound effect on the future of English literature. Determined to make the most of their gloomy, claustrophobic circumstances in the house, Lord Byron suggested that they all try their hand at writing a ghost story. It is worth noting what makes a ghost story effective: it is a mix of established narrative conventions, reworked vernacular myths or regional folklore, and informed scientific speculation with a penchant for the other-worldly or the supernatural. At the time, for example, this would have meant the possibility of life after death, the nature of demonic possession or haunting, and even the moral problem of whether or not evil is a real force in the world (and if it can be beaten).

The resulting speculative narratives, developed amidst the beautifully designed domestic circumstances of a hillside villa, continue to influence the English literary tradition today. John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” is considered the first vampire story in the English language, and Frankenstein—Mary Shelley’s vision of human resurrection achieved by way of electricity—has now reached the status of a modern myth.

There are some noteworthy parallels between the speculative narratives produced in this villa on the shores of Lake Geneva and the so-called House in the Sky in Los Angeles, where a similar small group of thinkers, writers, and theoreticians gathered to consider the end of the world. Those events are, in some ways, a strange but profoundly modern variation or even inversion of what happened in the Villa Diodati. Occurring not on the shores of Lake Geneva, for example, but in the hills of greater Los Angeles; not during a summer of unremittingly grey skies but in a climate of relentlessly clear weather; not, in the end, producing speculative ghost tales loosely based in science, or hypothesizing how humans might survive death itself, but outlining speculative plans for how an apocalyptic war might be waged and human extinction averted; and not under the shadow of volcanic ash spread from Mount Tambora, but in a haze of nuclear fallout, attempting to understand the complex global winds that would deliver that fatal debris around the planet.

The events at this atomic Diodati, as we might call it, also helped to set up both the narrative and the technical circumstances for simulation as a means for visualizing and describing speculative circumstances, or unrealized fictional narratives, and giving them analytic weight. If the residents of the Villa Diodati gave birth to fictions of monsters, then we might say that the residents of the House in the Sky produced a simulation of the end of the world.

In the summer of 1816, a group of young British writers rented a house on the shores of Lake Geneva, called the Villa Diodati. Their goal was to use it as a temporary home for several months of leisurely conversation and occasional writing, but also as base for short expeditions up into the nearby hills and mountains, where they hoped to experience the region’s glaciers and dramatic geological landscapes firsthand.

These writers were Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Polidori, and perhaps most consequently, the 18-year old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin—soon to become Mary Shelley, author of, among other books, Frankenstein.

The summer itself, in many ways, was a failure: due to the distant eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, which spread volcanic ash on winds across the entire northern hemisphere, their months in the Villa Diodati were marked not by sunshine and fresh mountain air but by near-continuous rain and violent thunderstorms. The skies were grey, the temperatures often frigid.

These meteorological events had a profound effect on the future of English literature. Determined to make the most of their gloomy, claustrophobic circumstances in the house, Lord Byron suggested that they all try their hand at writing a ghost story. It is worth noting what makes a ghost story effective: it is a mix of established narrative conventions, reworked vernacular myths or regional folklore, and informed scientific speculation with a penchant for the other-worldly or the supernatural. At the time, for example, this would have meant the possibility of life after death, the nature of demonic possession or haunting, and even the moral problem of whether or not evil is a real force in the world (and if it can be beaten).

The resulting speculative narratives, developed amidst the beautifully designed domestic circumstances of a hillside villa, continue to influence the English literary tradition today. John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” is considered the first vampire story in the English language, and Frankenstein—Mary Shelley’s vision of human resurrection achieved by way of electricity—has now reached the status of a modern myth.

There are some noteworthy parallels between the speculative narratives produced in this villa on the shores of Lake Geneva and the so-called House in the Sky in Los Angeles, where a similar small group of thinkers, writers, and theoreticians gathered to consider the end of the world. Those events are, in some ways, a strange but profoundly modern variation or even inversion of what happened in the Villa Diodati. Occurring not on the shores of Lake Geneva, for example, but in the hills of greater Los Angeles; not during a summer of unremittingly grey skies but in a climate of relentlessly clear weather; not, in the end, producing speculative ghost tales loosely based in science, or hypothesizing how humans might survive death itself, but outlining speculative plans for how an apocalyptic war might be waged and human extinction averted; and not under the shadow of volcanic ash spread from Mount Tambora, but in a haze of nuclear fallout, attempting to understand the complex global winds that would deliver that fatal debris around the planet.

The events at this atomic Diodati, as we might call it, also helped to set up both the narrative and the technical circumstances for simulation as a means for visualizing and describing speculative circumstances, or unrealized fictional narratives, and giving them analytic weight. If the residents of the Villa Diodati gave birth to fictions of monsters, then we might say that the residents of the House in the Sky produced a simulation of the end of the world.